Steve Lohr's comment in The New York Times on Tuesday November 4, titled "In Modeling Risk, the Human Factor was left out" makes for an interesting read. The blame for the financial meltdown is placed on those who thought they had covered all the angles in modelling financial markets, but who had forgotten the human factor.

However, he does not mention the providers of the technology. If guns had not been invented then people wouldn't get shot and without the development of computer technology and software, the financial engineering could not have taken place.

In 1987, the quant guys couldn’t handle massive, multi-variate models on their slow PCs, yet alone e-mail relatively small Supercalc spreadsheets to all and sundry.

Now SQL, SSPS and Excel, combined with Intel chips and the internet, give people tremendous computing power to produce models and an array of accompanying graphs to prove in glorious technicolor that all outcomes have been tested and therefore the computer’s output is right.

In addition, multiple recipients can now readily see these 50Mbyte models anywhere in the world on a 24/7 basis and be similarly enticed, thanks to e-mail, wi-fi and search engines.

As ever though, garbage in, garbage out or as Mr Lohr more accurately points out, not all the data to validate all the outcomes were input to these models despite the size of them. Forecasting, the daily returns of a large portfolio of multi-year mortgages would test even today’s laptops.

Perhaps the computer simply discourages critical, common-sense based thinking. People tend to believe everything they see on the internet. By contrast, a generation ago, people were told not to believe everything they read in newspapers.

But we've been here before. This financial crisis caused by misbehaving markets (as the models would have us believe) is a re-run of past crises of illiquid securities. The success of great minds and their models baffling mere mortals, was highlighted by the failure of LTCM which collapsed in 1998, just one year after two of its partners, Messrs Merton and Scholes got their Nobel economics prize for option theory.

Unfortunately, the financial regulators chose not to learn from this close call on the integrity of the financial system; financial engineering and its inherent weaknesses could continue unabated.

Now 10 years on from LTCM, and according to Moore's Law (chip capacity can double every 2 years) we now have around 2^5 the computing power that was available to the LTCM team. This should have given us the chance to make a 2^5 greater mess than the $4.6bn loss covered by the FED-orchestrated bailout in 1998.

So will we get away with just a 32x increase in bailout cost? It doesn't look like it at present, as markets talk in terms of trillions of dollars of CDS exposures and bank writedowns already total $702bn (Bloomberg).

But who knows, the net net cost might just be $117bn. In which case, if we escape with this low amount, then after the crisis, financial engineering can start again happy in the knowledge that in 2018, the cost of a bailout will be no more than 2^10 more than in 1998, at $4.7trillion.

Thursday, 6 November 2008

Monday, 13 October 2008

ICICI Bank disingenuousness

ICICI is parading the fact that Moody's is rating its UK subsidiary at Baa1.

Two things strike me; a) it's Moody's, the same outfit that had Kaupthing at Baa3 until as recently as October 8th and b) the rating is higher than Moody's FC rating for the Indian parent.

So it looks like the Baa1 rating includes some support from a higher rated entity - presumably the UK government. But did anyone see ICICI UK Ltd on HMG's "chosen few" list of 7 banks and 1 building society?

And the other rating agencies - both have ICICI India at BBB-/stable, with an A3 short-term rating. Furthermore, bank strength ratings are in the order of C and C-; these are weak for a bank.

So thanks to Moody's JDA (joint default assessment) scheme, which gives the UK branch a better rating (neither Fitch or S&P rate the UK entity and why would ICICI buy an extra rating if it's lower?), the management are trying to imply that all is well. For some reason, ICICI Ltd in Singapore does not get any uplift and is Baa2 according to Moody's but that is probably down to the Moody's JDA black box expectation of support from MAS.

The move to seek reaffirmations of the ICICI ratings from Moody's and S&P over the weekend is an unusual move and almost certainly requested by the company. The hurriedness is reflected in the S&P statement referring to "Bakerie" rather than the Bakrie group.

In conclusion, things may be well with ICICI India but there is no guarantee for the UK subsidiary. Things may well be well for the UK subsidiary too, although it does seem to have been more exposed to the shenanigans of international derivatives than the Parent in India.

What is not so good is management's apparent misunderstanding of ratings and structural sub-ordination and the implications this has for the advice management is giving to the world at large about its relative credit standing.

Two things strike me; a) it's Moody's, the same outfit that had Kaupthing at Baa3 until as recently as October 8th and b) the rating is higher than Moody's FC rating for the Indian parent.

So it looks like the Baa1 rating includes some support from a higher rated entity - presumably the UK government. But did anyone see ICICI UK Ltd on HMG's "chosen few" list of 7 banks and 1 building society?

And the other rating agencies - both have ICICI India at BBB-/stable, with an A3 short-term rating. Furthermore, bank strength ratings are in the order of C and C-; these are weak for a bank.

So thanks to Moody's JDA (joint default assessment) scheme, which gives the UK branch a better rating (neither Fitch or S&P rate the UK entity and why would ICICI buy an extra rating if it's lower?), the management are trying to imply that all is well. For some reason, ICICI Ltd in Singapore does not get any uplift and is Baa2 according to Moody's but that is probably down to the Moody's JDA black box expectation of support from MAS.

The move to seek reaffirmations of the ICICI ratings from Moody's and S&P over the weekend is an unusual move and almost certainly requested by the company. The hurriedness is reflected in the S&P statement referring to "Bakerie" rather than the Bakrie group.

In conclusion, things may be well with ICICI India but there is no guarantee for the UK subsidiary. Things may well be well for the UK subsidiary too, although it does seem to have been more exposed to the shenanigans of international derivatives than the Parent in India.

What is not so good is management's apparent misunderstanding of ratings and structural sub-ordination and the implications this has for the advice management is giving to the world at large about its relative credit standing.

Wednesday, 8 October 2008

Gordon Brown should copy HKMA

Given that the equity market is the most liquid, the most talked about and a key element in economic Lead Indicators, why doesn't HMG buy bank shares?

It can then make proper representation as a shareholder in the control of the business and can profit from its involvement.

Given that it is giving liquidity through the Bank of England, some equity upside is not too much to ask.

Unlike Mr Buffet, HMG should buy from the market and not take options on future performance. Furthermore, the preference share route is best avoided; these do not provide a cushion to a bank's equity price, but act as a penal charge on income. In the current environment of liability guarantees, the cushion to unsecured creditors afforded by the preference shares is simply not needed.

The common equity purchase plus judicious involvement in any rights issues or placings represent the best spur for confidence and allow the market to see the floor. All those investors now holding cash can then take a view.

In purchasing the equity, the trading criteria should be specific; e.g. it will be a potential buyer of bank shares if the price to book is say less than 0.35x and a potential seller if the price to book is over 0.65x. It will never sell more than 5% of its holding or 1% of the shares outstanding in the bank in any one day, and so on.

Does it work? Ask the Hong Kong Monetary Authority if their $15bn of share purchases on the Hong Kong stockmarket, over two weeks in August 1998, worked. I think it did, and they subsquently made a good profit. Perhaps there's some gecko lurking somewhere in Gordon waiting to emerge.

It can then make proper representation as a shareholder in the control of the business and can profit from its involvement.

Given that it is giving liquidity through the Bank of England, some equity upside is not too much to ask.

Unlike Mr Buffet, HMG should buy from the market and not take options on future performance. Furthermore, the preference share route is best avoided; these do not provide a cushion to a bank's equity price, but act as a penal charge on income. In the current environment of liability guarantees, the cushion to unsecured creditors afforded by the preference shares is simply not needed.

The common equity purchase plus judicious involvement in any rights issues or placings represent the best spur for confidence and allow the market to see the floor. All those investors now holding cash can then take a view.

In purchasing the equity, the trading criteria should be specific; e.g. it will be a potential buyer of bank shares if the price to book is say less than 0.35x and a potential seller if the price to book is over 0.65x. It will never sell more than 5% of its holding or 1% of the shares outstanding in the bank in any one day, and so on.

Does it work? Ask the Hong Kong Monetary Authority if their $15bn of share purchases on the Hong Kong stockmarket, over two weeks in August 1998, worked. I think it did, and they subsquently made a good profit. Perhaps there's some gecko lurking somewhere in Gordon waiting to emerge.

Wednesday, 1 October 2008

Debt for Equity - not liabilities to governments

There is a concern that banks have stopped lending. Is this because there are no solid borrowers or is it because lenders have lost faith as a result of arbitary changes to property rights and bankruptcy laws?

Banks will not advance money if they no longer see the equity of the borrower taking the first hit. If there is no first hit to be taken, then the banks must assume that they are pari passu with equity holders.

The main problem facing markets is that banks are facing immediate heavy losses arising from derivative financial contracts. Banks balance sheets are not designed for catastrophic losses of equity, but they can absorb up to 10% to 15% total losses on their loan book over say 5 years. This is equivalent to a 50% to 66% recovery on a bad loan book equivalent to 30% of the total loan book. Banks with non-performing assets = 10% of total assets will struggle. If the ratio reaches 20%, the bank will most likely fail.

For example, assume a typical bank with common equity of 6% of assets and a pre-tax, pre-provision ROA of 3.5%. If in any one year 15% of the loan book is non-performing then ppROA will fall to say 3%. Provisions and losses at 33% of these NPA reduce overall ROA to 0% and eat into equity to the value of 2% of assets, reducing equity to 4% of assets. The bank has an equity issue of say 1 new share for every one held but as the Price to Book Value will be <<1.0x, say 0.5x, the equity base only recovers to where it was before, at 6% assets.

If the same happens the following year, then shareholders will once again need to chuck money at the bank equivalent to 2% of the asset base until the problem eases.

But if I don't recover 67cents on the dollar and/or if the NPA ratio is higher, then the equity will be depleted by much more than 2% of the asset base. In addition, the ppROA will be adversely impacted by funding costs and the price to book ratio, ahead of the new share issue, will be even more bleak.

The forthcoming settlement of AIG, Fannie & Freddie, and Lehman CDS contracts means that we will get some market clearing prices on the bad assets. Then buyers and suppliers of capital will magically reappear because the calculations outlined above can be done with more certainty.

However, bank recapitalisation also requires time. As alluded to above, banks take the hits year by year and that is because the work out of loans or recovery of collateral are also time consuming processes. Furthermore, as these bad loans were "held to maturity" assets, and thus valued with some discretion, the banks had a chance to blend internally generated capital and external equity injections to restore the bank to rude health.

By contrast, the upcoming CDS auctions could be traumatic as we are trying to estimate in a few days the recovery value of the assets and the liabilities of four intertwined businesses. This is before the people now controlling the failed entities have barely started work on assessing the real assets of the businesses.

Unfortunately there is massively more value in the CDS being settled by auction than there is in the real assets of the business. Maybe 10x more derivatives traded than underlying assets, maybe much more. Mispricing the CDS values by 5cents on the dollar is equivalent to being 50% wrong on the value of the real assets.

But unfortunately the market price established will need to be used by the banks and this will almost certainly throw up some permanent impairments to their "held to maturity" loans. The chance for banks to smooth their way back to profits will have disappeared.

There seem to be three routes forward assuming banks remain in the private sector;

i) BIS and/or Fed relax the banks' capital criteria,

ii) another major overhaul of mark to market accounting is required or

iii) creditors take equity.

The purest route forward to offset the instant value destruction derived from the CDS auction would seem to be the creation of instant equity. In other words, there must be a mechanism for the instant swap of debt for equity.

But such changes cannot happen if governments have guaranteed all non-consumer deposits and liabilities, or if indeed the government has already split the balance sheet up.

As noted earlier, banks, in effect, already believe that they are no better off than equity holders which is why they are not lending. However, it is not the uncertainty of the credit market that makes holding equity unattractive but the unpredictability of government actions with respect to any holder of a bank liability.

At least with another bank's equity in their pockets, a bank then owns (albeit a very large amount) a homogeneous, transparently-priced security for which there is a liquid market - as long as the government doesn't interfere.

And finally, the conflict between going concern principles and fair value accounting can, in my view, best be resolved if liabilities are valued at the higher of par or market value. (Pension liabilities should be discounted at long-term government bond yields). There would need to be a balancing quasi-financial asset, but at least the ridiculous state of affairs where a struggling bank can show an enhanced equity valuation because the market discount to par of its own capital instruments are credited to equity, would disappear.

Invexit

Banks will not advance money if they no longer see the equity of the borrower taking the first hit. If there is no first hit to be taken, then the banks must assume that they are pari passu with equity holders.

The main problem facing markets is that banks are facing immediate heavy losses arising from derivative financial contracts. Banks balance sheets are not designed for catastrophic losses of equity, but they can absorb up to 10% to 15% total losses on their loan book over say 5 years. This is equivalent to a 50% to 66% recovery on a bad loan book equivalent to 30% of the total loan book. Banks with non-performing assets = 10% of total assets will struggle. If the ratio reaches 20%, the bank will most likely fail.

For example, assume a typical bank with common equity of 6% of assets and a pre-tax, pre-provision ROA of 3.5%. If in any one year 15% of the loan book is non-performing then ppROA will fall to say 3%. Provisions and losses at 33% of these NPA reduce overall ROA to 0% and eat into equity to the value of 2% of assets, reducing equity to 4% of assets. The bank has an equity issue of say 1 new share for every one held but as the Price to Book Value will be <<1.0x, say 0.5x, the equity base only recovers to where it was before, at 6% assets.

If the same happens the following year, then shareholders will once again need to chuck money at the bank equivalent to 2% of the asset base until the problem eases.

But if I don't recover 67cents on the dollar and/or if the NPA ratio is higher, then the equity will be depleted by much more than 2% of the asset base. In addition, the ppROA will be adversely impacted by funding costs and the price to book ratio, ahead of the new share issue, will be even more bleak.

The forthcoming settlement of AIG, Fannie & Freddie, and Lehman CDS contracts means that we will get some market clearing prices on the bad assets. Then buyers and suppliers of capital will magically reappear because the calculations outlined above can be done with more certainty.

However, bank recapitalisation also requires time. As alluded to above, banks take the hits year by year and that is because the work out of loans or recovery of collateral are also time consuming processes. Furthermore, as these bad loans were "held to maturity" assets, and thus valued with some discretion, the banks had a chance to blend internally generated capital and external equity injections to restore the bank to rude health.

By contrast, the upcoming CDS auctions could be traumatic as we are trying to estimate in a few days the recovery value of the assets and the liabilities of four intertwined businesses. This is before the people now controlling the failed entities have barely started work on assessing the real assets of the businesses.

Unfortunately there is massively more value in the CDS being settled by auction than there is in the real assets of the business. Maybe 10x more derivatives traded than underlying assets, maybe much more. Mispricing the CDS values by 5cents on the dollar is equivalent to being 50% wrong on the value of the real assets.

But unfortunately the market price established will need to be used by the banks and this will almost certainly throw up some permanent impairments to their "held to maturity" loans. The chance for banks to smooth their way back to profits will have disappeared.

There seem to be three routes forward assuming banks remain in the private sector;

i) BIS and/or Fed relax the banks' capital criteria,

ii) another major overhaul of mark to market accounting is required or

iii) creditors take equity.

The purest route forward to offset the instant value destruction derived from the CDS auction would seem to be the creation of instant equity. In other words, there must be a mechanism for the instant swap of debt for equity.

But such changes cannot happen if governments have guaranteed all non-consumer deposits and liabilities, or if indeed the government has already split the balance sheet up.

As noted earlier, banks, in effect, already believe that they are no better off than equity holders which is why they are not lending. However, it is not the uncertainty of the credit market that makes holding equity unattractive but the unpredictability of government actions with respect to any holder of a bank liability.

At least with another bank's equity in their pockets, a bank then owns (albeit a very large amount) a homogeneous, transparently-priced security for which there is a liquid market - as long as the government doesn't interfere.

And finally, the conflict between going concern principles and fair value accounting can, in my view, best be resolved if liabilities are valued at the higher of par or market value. (Pension liabilities should be discounted at long-term government bond yields). There would need to be a balancing quasi-financial asset, but at least the ridiculous state of affairs where a struggling bank can show an enhanced equity valuation because the market discount to par of its own capital instruments are credited to equity, would disappear.

Invexit

Friday, 19 September 2008

Investment bank advice to Fed - SOS

Funny how, as the investment banks fell one by one, and as pressure mounted on Goldmans, the governments of the world suddenly took action. Just in time, as one of the most successful pedlars of derivatives and toxic debt products, and a master of trading and short-selling, might have gone bust.

Why governments seek advice from investment banks, the scourge of the modern world, is difficult to understand. For these banks there are yet more fees, coupled with ability to steer their clients towards maintaining loose regulation for their activities. But should not advice on the real economy, come from the commercial banks who handle real deposits and who make loans to material entities?

So instead of allowing their alma matere to be wiped out, to the future benefit of all, these government advisers decide it's time to get their political poodles to do something - save our souls.

(Invexit)

Why governments seek advice from investment banks, the scourge of the modern world, is difficult to understand. For these banks there are yet more fees, coupled with ability to steer their clients towards maintaining loose regulation for their activities. But should not advice on the real economy, come from the commercial banks who handle real deposits and who make loans to material entities?

So instead of allowing their alma matere to be wiped out, to the future benefit of all, these government advisers decide it's time to get their political poodles to do something - save our souls.

(Invexit)

Friday, 11 July 2008

Singapore's recession reporting

Singapore has been in technical recession as of the end of March 2008 and based on this week's flash estimate of Q2, GDP will have shrunk again. So has the R word featured in the media?

Press releases from the MTI steer the journalists and market players to look at growth. The magic of seasonal adjustment makes the quarter on quarter numbers still look strong while the base effect impacting the year on year, quarterly numbers keeps the increment positive. Coupled with the government sticking to its 4% to 6% growth forecast for 2008 and everyone is happy. A cynic might ask if the focus on the incremental rather than the absolute GDP numbers is in some way related to the performance linked pay of Singapore's civil servants?

Back to the numbers ...

GDP at 2000 market prices in SGD million (source ESS)

Q2 2007 57,019.4, Q3 2007 58,842.3, Q4 2007 58,538.6, Q1 2008 58,362.7.

So Q1 08 is lower than Q4 07, which is lower than Q3 07. Technical recession?

And the "good news" flash estimate for Q2 2008 is growth of 1.9%. Based on Q2 07, this actually points to a further fall in output to around SGD58.1bn for Q2 2008.

The inflation rate has "arrested" some attention in the media, which at 7.5% yoy to May 2008 is uncomfortably high and this is despite a currency being held at the strong end of its trade-weighted range. Comments on the decline in labour productivity have been few and far between. The country wants the influx of foreign workers to continue; unfortunately they are failing to stimulate the economy.

Journalists are commenting on the very low interest rates in Singapore, mainly because savings rates for depositors are at derisory levels. With a full blown recession underway, low interest rates in Singapore are desirable. Despite the minimal cost of funds, the rate of monetary growth has been declining in recent months from the >20% levels seen in much of 2007 and was down to 9.0% in the year to May 2008.

So why is money attracted to Singapore? Is it the safe haven of the East? Property prices have had a good run supported by foreign investors, but at what stage, if at all, do the investors react to the weak growth and high negative real interest rates and dump SGD assets? Can energy-intensive Singapore survive in a world of high oil and food prices? While the great man is still with us, the chances are good.

Press releases from the MTI steer the journalists and market players to look at growth. The magic of seasonal adjustment makes the quarter on quarter numbers still look strong while the base effect impacting the year on year, quarterly numbers keeps the increment positive. Coupled with the government sticking to its 4% to 6% growth forecast for 2008 and everyone is happy. A cynic might ask if the focus on the incremental rather than the absolute GDP numbers is in some way related to the performance linked pay of Singapore's civil servants?

Back to the numbers ...

GDP at 2000 market prices in SGD million (source ESS)

Q2 2007 57,019.4, Q3 2007 58,842.3, Q4 2007 58,538.6, Q1 2008 58,362.7.

So Q1 08 is lower than Q4 07, which is lower than Q3 07. Technical recession?

And the "good news" flash estimate for Q2 2008 is growth of 1.9%. Based on Q2 07, this actually points to a further fall in output to around SGD58.1bn for Q2 2008.

The inflation rate has "arrested" some attention in the media, which at 7.5% yoy to May 2008 is uncomfortably high and this is despite a currency being held at the strong end of its trade-weighted range. Comments on the decline in labour productivity have been few and far between. The country wants the influx of foreign workers to continue; unfortunately they are failing to stimulate the economy.

Journalists are commenting on the very low interest rates in Singapore, mainly because savings rates for depositors are at derisory levels. With a full blown recession underway, low interest rates in Singapore are desirable. Despite the minimal cost of funds, the rate of monetary growth has been declining in recent months from the >20% levels seen in much of 2007 and was down to 9.0% in the year to May 2008.

So why is money attracted to Singapore? Is it the safe haven of the East? Property prices have had a good run supported by foreign investors, but at what stage, if at all, do the investors react to the weak growth and high negative real interest rates and dump SGD assets? Can energy-intensive Singapore survive in a world of high oil and food prices? While the great man is still with us, the chances are good.

Wednesday, 14 May 2008

Bradford & Bingley - stewards' enquiry needed

Never mind what Steven Crawshaw said to the markets on 14th April regarding the likelihood of a rights issue, what he said on the morning of 22nd April, in the interim management statement was even more misleading. In this he comments on the capital base and funding in the same sentence but with no mention of the capital ratios being at risk.

"The first quarter of 2008 has seen excellent growth in our retail deposit base. Bradford & Bingley has a strong capital base and has funded its business activities through 2008 and into 2009. We have a focused strategy, and a business model that is adaptable to changing market conditions."

Given the deep discount of the rights issue - the new shares offered at 82p compared with the prior close of 158p - one wonders why an underwriter is needed, especially as management gives the impression that capital is not urgently needed.

The recent price movements of B&B relative to those of the other financial desperados - A&L and Barclays - suggest that a bit of window dressing ahead of this rights issue might have been underway. Have the underwriters been earning their fees? A steward's enquiry would be most welcome.

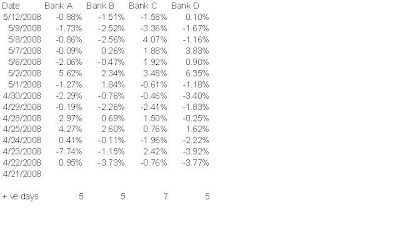

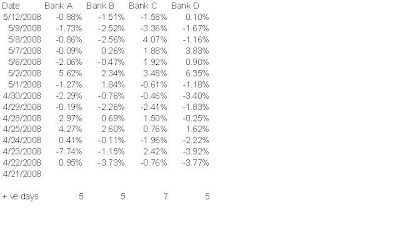

The table above takes the daily price movement (ln (Px/Px-1)). It uses using prices from Yahoo and so ends on Monday 12th. Bank A is Alliance & Leicester, B is Barclays, C is Bradford& Bingley and D is HBOS - which of course already has announced a rights issue.

And the bank with the most price rises over the fourteen days - well B&B of course.

"The first quarter of 2008 has seen excellent growth in our retail deposit base. Bradford & Bingley has a strong capital base and has funded its business activities through 2008 and into 2009. We have a focused strategy, and a business model that is adaptable to changing market conditions."

Given the deep discount of the rights issue - the new shares offered at 82p compared with the prior close of 158p - one wonders why an underwriter is needed, especially as management gives the impression that capital is not urgently needed.

The recent price movements of B&B relative to those of the other financial desperados - A&L and Barclays - suggest that a bit of window dressing ahead of this rights issue might have been underway. Have the underwriters been earning their fees? A steward's enquiry would be most welcome.

The table above takes the daily price movement (ln (Px/Px-1)). It uses using prices from Yahoo and so ends on Monday 12th. Bank A is Alliance & Leicester, B is Barclays, C is Bradford& Bingley and D is HBOS - which of course already has announced a rights issue.

And the bank with the most price rises over the fourteen days - well B&B of course.

Saturday, 9 February 2008

Premier League Irony

7th February 2008, British newspapers carry pictures and stories of the Munich air crash on 6th February 1958 and the commemorative services held 50 years later for the 23 people who died.

8th February 2008, British newspapers carry stories about the Premier League's plans to play fixtures overseas.

And I thought bankers had short memories - although memory is an inconvenience when money is involved. However, at least banks and other financial institutions now operate policies that limit the number of employees that can fly on any single aircraft - a lesson learned the tragic way by UBS as a result of the Swissair MD-11 crash of September 2, 1998.

As for the Premier League's plan, I haven't even started on carbon footprints, the potential alienation and loss of domestic audience etc.

8th February 2008, British newspapers carry stories about the Premier League's plans to play fixtures overseas.

And I thought bankers had short memories - although memory is an inconvenience when money is involved. However, at least banks and other financial institutions now operate policies that limit the number of employees that can fly on any single aircraft - a lesson learned the tragic way by UBS as a result of the Swissair MD-11 crash of September 2, 1998.

As for the Premier League's plan, I haven't even started on carbon footprints, the potential alienation and loss of domestic audience etc.

Friday, 8 February 2008

Where next for AAA ratings?

As the rating agencies announce reviews of their methodologies, it goes without saying that there will be more tinkering and more rating scales rather than a return to the simplicity of the single trade-based credit scale borrowed by the original bond rating agencies.

The main problem is that AAA is not what it says on the label. Obviously therefore, "AAA" should be sub-divided into AAA1, AAA2 and AAA3. This would give the agencies more potential rating moves on which to comment and users of the ratings would then be aware of which entities were "weakly positioned in the AAA range" rather than simply being a "risk-free" investment.

However, some might feel that, like the UK's school examination system, this is a dumbing down of the top standard. A solution to this concern would be to create "AAAA", the new top standard which, in polo shirt-sizing jargon, we could perhaps call "4XA".

Alternatively, we could introduce the prefix "s" to a rating thus adding to the existing 30+ rating scales that Moody's, for example, currently operates. The "s" would stand for spreadsheet and would alert investors to the fact that the ratings have been derived from models recently dreamed up by quant PhDs and the newly created entities are simply boilerplate companies run by small back office teams. These "s.AAA" ratings could then be distinguished from earned, tangible AAA ratings. How can a CDO be sensibly compared to the likes of Germany, Singapore, General Electric and Toyota, whose enduring managements can demonstrate a 15+ year track record of consistent performance and, in the case of the two companies, are supported by net worth of over $100bn.

And what of the USA? Investors have accepted AAA as representing the "gold standard" of ratings and US Treasuries, rated AAA, are the ultimate risk-free investment, Unfortunately foreign currency-based investors in money-good UST have still lost some 7% p.a. over the last seven years when the USD is measured against a global basket of currencies. Perhaps if the USD currency was a reliable store of wealth and behaved more like a gold standard then the quality of the rest of the USD-based financial system might also improve.

The main problem is that AAA is not what it says on the label. Obviously therefore, "AAA" should be sub-divided into AAA1, AAA2 and AAA3. This would give the agencies more potential rating moves on which to comment and users of the ratings would then be aware of which entities were "weakly positioned in the AAA range" rather than simply being a "risk-free" investment.

However, some might feel that, like the UK's school examination system, this is a dumbing down of the top standard. A solution to this concern would be to create "AAAA", the new top standard which, in polo shirt-sizing jargon, we could perhaps call "4XA".

Alternatively, we could introduce the prefix "s" to a rating thus adding to the existing 30+ rating scales that Moody's, for example, currently operates. The "s" would stand for spreadsheet and would alert investors to the fact that the ratings have been derived from models recently dreamed up by quant PhDs and the newly created entities are simply boilerplate companies run by small back office teams. These "s.AAA" ratings could then be distinguished from earned, tangible AAA ratings. How can a CDO be sensibly compared to the likes of Germany, Singapore, General Electric and Toyota, whose enduring managements can demonstrate a 15+ year track record of consistent performance and, in the case of the two companies, are supported by net worth of over $100bn.

And what of the USA? Investors have accepted AAA as representing the "gold standard" of ratings and US Treasuries, rated AAA, are the ultimate risk-free investment, Unfortunately foreign currency-based investors in money-good UST have still lost some 7% p.a. over the last seven years when the USD is measured against a global basket of currencies. Perhaps if the USD currency was a reliable store of wealth and behaved more like a gold standard then the quality of the rest of the USD-based financial system might also improve.

Thursday, 10 January 2008

Rating agencies are USD muppets

For too long the rating agencies have dished out foreign currency ratings with the USD deemed as the ultimate foreign currency. While sovereign rating analysts are quick to point out the failings of emerging market economies that adopt poor economic, fiscal and monetary policy and which often lead to a depreciation of the local currency against the USD, the 7% annual loss for the last six years in the USD against a global currency basket has been conveniently ignored. For global investors, the USD depreciation has been a major loss of value.

Of course, printing money to destroy its value is the way for any government to reduce the burden of debt, but the global rating agencies do the world a disservice if they only look at life through greenback tinted spectacles.

While rating agencies have sought to distance themselves from valuation, all their models for structured finance, work backwards from an assumed valuation or recovery given default. Thus while many AAA rated obligations have been downgraded, few have defaulted - the downgrades generally representing the risk of greater loss.

So Moody's et al, hurry up and downgrade likely value destruction wherever it is. There is no excuse not to use a global currency index; if spreadsheets can support your quantitative risk models, running a foreign currency basket programme is a doddle. If foreign currency ratings aren't based on the most reliable currency benchmark (absent a gold standard) then outcomes too will be second rate.

Of course, printing money to destroy its value is the way for any government to reduce the burden of debt, but the global rating agencies do the world a disservice if they only look at life through greenback tinted spectacles.

While rating agencies have sought to distance themselves from valuation, all their models for structured finance, work backwards from an assumed valuation or recovery given default. Thus while many AAA rated obligations have been downgraded, few have defaulted - the downgrades generally representing the risk of greater loss.

So Moody's et al, hurry up and downgrade likely value destruction wherever it is. There is no excuse not to use a global currency index; if spreadsheets can support your quantitative risk models, running a foreign currency basket programme is a doddle. If foreign currency ratings aren't based on the most reliable currency benchmark (absent a gold standard) then outcomes too will be second rate.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)